Research Project Highlight: Bogotá Urban Tree Cover Research Project

In 2011-2012 CitiNature conducted a 9-month study of the street-tree canopy in Bogotá, Colombia. Our findings were starkly revealing and showed a stunning contrast between wealthy neighborhoods and poor neighborhoods in terms of tree coverage. We generated the first set of published data on street-tree inequality in any developing-world city, conclusively demonstrating the green divide in Bogotá and providing a basic model for stree-tree equity studies in other cities around the world

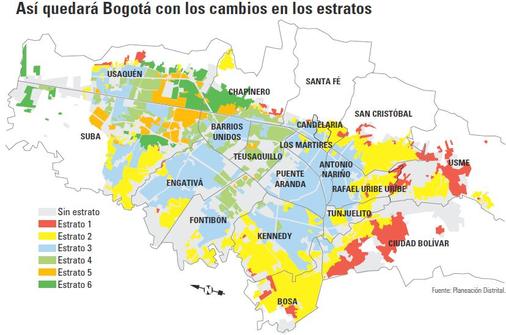

A map of Bogota showing the economic 'strata' of the city.

In all my writing, the importance of trees in creating a quality urban life has been a constant theme. The benefits of trees, especially street trees, range from environmental improvements (urban cooling and cleaner air) to social benefits (stress reduction and neighborhood cohesion). Countless studies have documented the transformative power of urban trees. And what's more, most people would agree that trees are beautiful. But despite their importance, trees are not a resource shared equally in most cities of the world. .

Even a brief stay in Bogotá will make one aware of the dramatic change in the look of streets as one moves across socioeconomic lines. The change is not striking simply in respect to the style and quality of home and street construction, but equally dramatic in the almost complete lack of street trees and vegetation in

neighborhoods at the lower socioeconomic levels.

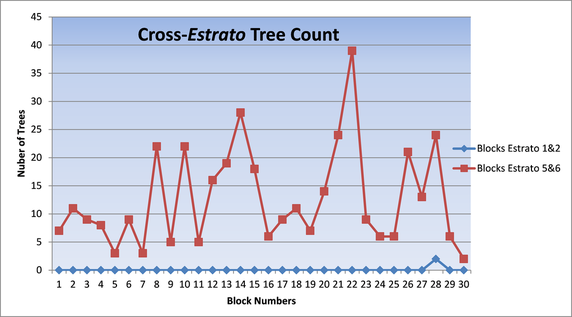

Bogota is a city officially divided into socioeconomic units called estrato (strata) numbered from 1 to 6. Estratos 5 and 6 represent the wealthiest neighborhoods, and 1 and 2 the poorest. To document the tree disparities across estrato, I conducted a tree survey with a random sampling of 30 streets in the wealthiest part of the city (estratos 5 and 6) and 30 in the poorest parts of the city (estratos 1 and 2). Below is a chart showing the data. The survey results makes it clear that the tree gap across socioeconomic lines in Bogotá is uniform and stark. Generally speaking, the streets in the lowest estrato of Bogotá are barren, while the streets in the wealthy neighborhoods have a healthy canopy of trees

Even a brief stay in Bogotá will make one aware of the dramatic change in the look of streets as one moves across socioeconomic lines. The change is not striking simply in respect to the style and quality of home and street construction, but equally dramatic in the almost complete lack of street trees and vegetation in

neighborhoods at the lower socioeconomic levels.

Bogota is a city officially divided into socioeconomic units called estrato (strata) numbered from 1 to 6. Estratos 5 and 6 represent the wealthiest neighborhoods, and 1 and 2 the poorest. To document the tree disparities across estrato, I conducted a tree survey with a random sampling of 30 streets in the wealthiest part of the city (estratos 5 and 6) and 30 in the poorest parts of the city (estratos 1 and 2). Below is a chart showing the data. The survey results makes it clear that the tree gap across socioeconomic lines in Bogotá is uniform and stark. Generally speaking, the streets in the lowest estrato of Bogotá are barren, while the streets in the wealthy neighborhoods have a healthy canopy of trees

Graph of the data comparing wealthy Estratos 5 & 6 with poor Estratos 1&2.

But why does this green divide exist? The observant visitor to Bogotá will notice that a formidable barrier to street-tree planting exists in much of the city: the changing structure of the streets as one moves from the higher estratos to the lower. This change can be very abrupt. Simply crossing a single street can bring you into a markedly different environment. One key to the difference is the structure of sidewalks and the allocation (or not) of a planting median between the sidewalk and street. The lack of a planting median is one of the hallmarks of the lower estratos in Bogotá. Not only are the structure of the houses different, but the streets in the lower strata are almost always without a green median between the sidewalk and the street, and hence are without room for trees. They are urban deserts by design.

The inferior design of low-estrato streets in Bogotá has resulted from mass migration into the city under the neglectful watch of dysfunctional city and national governments. In the period from 1960 to 2012, Bogotá's population increased from slightly over 1 million inhabitants to nearly 10 million today. During much of this same period, Bogotá's government was ill equipped in terms of resources, organization, and capabilities (and interest, many would say) to manage the mass influx. Large swathes of this city were, therefore, developed without any government regulation. With no goverment involvement, private 'pirate' developers created most lower-class neighborhoods in this city. To maximize their profits and keep costs low, land was divided into as many lots as possible, leaving only a bare minimum of space for public amenities. Streets in these neighborhoods are very narrow, and sidewalks, where they exist, are extremely narrow.

The inferior design of low-estrato streets in Bogotá has resulted from mass migration into the city under the neglectful watch of dysfunctional city and national governments. In the period from 1960 to 2012, Bogotá's population increased from slightly over 1 million inhabitants to nearly 10 million today. During much of this same period, Bogotá's government was ill equipped in terms of resources, organization, and capabilities (and interest, many would say) to manage the mass influx. Large swathes of this city were, therefore, developed without any government regulation. With no goverment involvement, private 'pirate' developers created most lower-class neighborhoods in this city. To maximize their profits and keep costs low, land was divided into as many lots as possible, leaving only a bare minimum of space for public amenities. Streets in these neighborhoods are very narrow, and sidewalks, where they exist, are extremely narrow.

The problem of the structure of low-strata neighborhoods hangs heavily over efforts to improve the urban environment for the poor, and in particular efforts to increase street-tree cover in Bogotá. As nearly half of Bogotá's neighborhoods arose from pirate developments, it seems to many that these areas will be permanently treeless. A rebalancing of the tree population in Bogotá’s streets will require strong and effective government and a commitment to focus on the streets that dominate the lives of more than half the population of this city.

To get things moving, highly visible pilot projects should be launched, in conjunction with community organization and green education campaigns, to demonstrate the great improvements in quality of life that green streets can bring. As the streets of most neighborhoods don’t provide much space for trees, innovative and low-cost solutions that provide some of the benefits of trees may be adopted, such as green roofs and vine-covered walls and canopies. However, in many cases as streets are paved for the first time, or repaved, redesigns can be implemented that include planting spaces for trees. In many areas, streets can be pedestrianized, which would allow ample space for canopy-forming trees to be planted. Successful projects showing how city life can be transformed will lead to further interest and belief by the public in the benefits of tree-lined streets. This dynamic city, with its mild and favorable climate, has what it takes to become one of the greenest and most beautiful in South America.

To get things moving, highly visible pilot projects should be launched, in conjunction with community organization and green education campaigns, to demonstrate the great improvements in quality of life that green streets can bring. As the streets of most neighborhoods don’t provide much space for trees, innovative and low-cost solutions that provide some of the benefits of trees may be adopted, such as green roofs and vine-covered walls and canopies. However, in many cases as streets are paved for the first time, or repaved, redesigns can be implemented that include planting spaces for trees. In many areas, streets can be pedestrianized, which would allow ample space for canopy-forming trees to be planted. Successful projects showing how city life can be transformed will lead to further interest and belief by the public in the benefits of tree-lined streets. This dynamic city, with its mild and favorable climate, has what it takes to become one of the greenest and most beautiful in South America.

Consulting Project Highlight: El Fondo Acción

El Fondo para la Acción Ambiental y la Niñez (Fondo Acción) is a highly-respected Colombian environmental NGO supported by an endowment from the government of the United States.

Fondo Acción selects and funds high impact programs and projects in two priority thematic areas: conservation and sustainable development; and early childhood protection and development.

I worked with the 'Fondo' on two projects during 2011 and 2012. Here I will describe the consulting work I did for the 'Programa para el Desarrollo de Capacidades en Ecoturismo Comunitario', a program to help develop the capacity of community-run ecotourism businesses in Colombian national parks.

Fondo Acción selects and funds high impact programs and projects in two priority thematic areas: conservation and sustainable development; and early childhood protection and development.

I worked with the 'Fondo' on two projects during 2011 and 2012. Here I will describe the consulting work I did for the 'Programa para el Desarrollo de Capacidades en Ecoturismo Comunitario', a program to help develop the capacity of community-run ecotourism businesses in Colombian national parks.

The Lodge.

In this project, I worked closely with the very talented Ann Marie Steffa Ávila to help raise the business capabilities of a community ecotourism enterprise in the rather remote Iguaque National Park in the department of Boyacá in the high Andes of central Colombia. Despite incredible natural beauty on all sides and impressive wildlife (a remarkable variety of birds), capacity utilization at the lodge was far too low at almost all times of the year. The community enterprise was not a viable business. I worked to create a compelling story and designed the first informational website to allow potential visitors a glimpse of what was on offer. The aim: to raise visibility and increase visits by both Colombian and international ecotourists.

You can visit the Colombian National Parks website about the magical Iguaque here: http://www.parquesnacionales.gov.co/PNN/portel/libreria/php/decide.php?patron=01.022907

The Naturar Lodge website is here: http://naturariguaque.weebly.com/

You can visit the Colombian National Parks website about the magical Iguaque here: http://www.parquesnacionales.gov.co/PNN/portel/libreria/php/decide.php?patron=01.022907

The Naturar Lodge website is here: http://naturariguaque.weebly.com/

Urban Greening Project Highlight: CitiNature's Pilot Greening Project in New York City

The indomitable Mr. Ng on watch.

CitiNature's first major project began in Forest Hills, Queens, New York in 2002. When I started work here, I named the project "the kibbutz" because of the proximity of a synagogue, Young Israel, which was directly adjacent to the site. It was not an auspicious beginning. Only piles of junk and a few stalks of sickly-looking mugwort peeking through met the eye, but I was mesmerized. This crude chunk of urban blight was in my eyes a beautiful oasis-to-be, a string of islands of trees, bushes and flowers - a place where people would enjoy the soothing colors of nature. It was a blank canvas with a large captive audience of pedestrians. Yellowstone Blvd. is a major thoroughfare in this area, and hundreds of people (and even more cars) pass by daily.

The idyllic vision collided, however, with some unpleasant realities. The dozens of loads of junk I started to remove was not just on the surface. The ground was literally poisoned with toxic wastes of all sorts, including many batteries, paint cans (with paint still inside or leaking out) and an array of other surprisingly nasty stuff. About 8 inches under the surface was a layer of asphalt (decades ago this area had been paved over) and below that large chunks of cement left behind from some ancient construction project. There was very little soil to work with.

The idyllic vision collided, however, with some unpleasant realities. The dozens of loads of junk I started to remove was not just on the surface. The ground was literally poisoned with toxic wastes of all sorts, including many batteries, paint cans (with paint still inside or leaking out) and an array of other surprisingly nasty stuff. About 8 inches under the surface was a layer of asphalt (decades ago this area had been paved over) and below that large chunks of cement left behind from some ancient construction project. There was very little soil to work with.

It's remarkable what can survive and thrive in construction rubble.

Watching my actions from his building next door, Kee Man Ng (pictured above) introduced himself and told me about his history with this site. He had always wanted to clean it up, but felt hindered by lack of any support, no idea of who owned the land, and a lack of confidence, I think, in his adopted English language (he had moved to New York from Hong Kong). We swiftly became steadfast partners and undertook an excavation. With pickaxes we pounded our way through the asphalt, removed it and most of the chunks of concrete buried under the surface, and then beheld our slightly sunken bed of clay, sand, and whatever dust had settled on the area over the years.

The growing medium at our disposal needed help. I had kept all the mugwort I'd yanked out of the ground, and having dried it, I mixed it and whatever other green matter I could find into the soil. The nearby Home Depot had many visits from me, carrying away dozens of bags of topsoil and mulch. Before long, a reasonable substrate of soil was covering this first parcel of land (out of a total of 8), and I started planting trees, bushes and wildflowers. The National Arbor Day Foundation, an incredible resource, provided many of the first trees and bushes at virtually no cost. The wildflowers soon sprouted, and with water and a little fertilizer, a lush bed of green and color filled this space. This is when the community really began to notice and get interested. Attitudes changed from "someone else should do that" or "who authorized you to do this?" to general appreciation and donations. Over the coming years, with a huge amount of work by the team (myself, Mr. Ng, and Bob Newell), the gardens grew and flourished and have become a bit of a neighborhood institution. You can still see Mr. Ng watering the gardens in the evening and Bob carefully tending the perennials he's lovingly planted.

The growing medium at our disposal needed help. I had kept all the mugwort I'd yanked out of the ground, and having dried it, I mixed it and whatever other green matter I could find into the soil. The nearby Home Depot had many visits from me, carrying away dozens of bags of topsoil and mulch. Before long, a reasonable substrate of soil was covering this first parcel of land (out of a total of 8), and I started planting trees, bushes and wildflowers. The National Arbor Day Foundation, an incredible resource, provided many of the first trees and bushes at virtually no cost. The wildflowers soon sprouted, and with water and a little fertilizer, a lush bed of green and color filled this space. This is when the community really began to notice and get interested. Attitudes changed from "someone else should do that" or "who authorized you to do this?" to general appreciation and donations. Over the coming years, with a huge amount of work by the team (myself, Mr. Ng, and Bob Newell), the gardens grew and flourished and have become a bit of a neighborhood institution. You can still see Mr. Ng watering the gardens in the evening and Bob carefully tending the perennials he's lovingly planted.