Characteristic Portland house with vegetable garden out front.

Characteristic Portland house with vegetable garden out front. Soon after arrival I recognized how unique this city is in the United States. Portland capitalizes on its assets in a way that creates a flourishing and very livable city - the best I've seen in any major US city. It offers a vision of what a medium-sized American city can be with the right policies, planning, and execution. It's a world apart from the typical American city, both in its well-designed urban environment and its stunning natural surroundings.

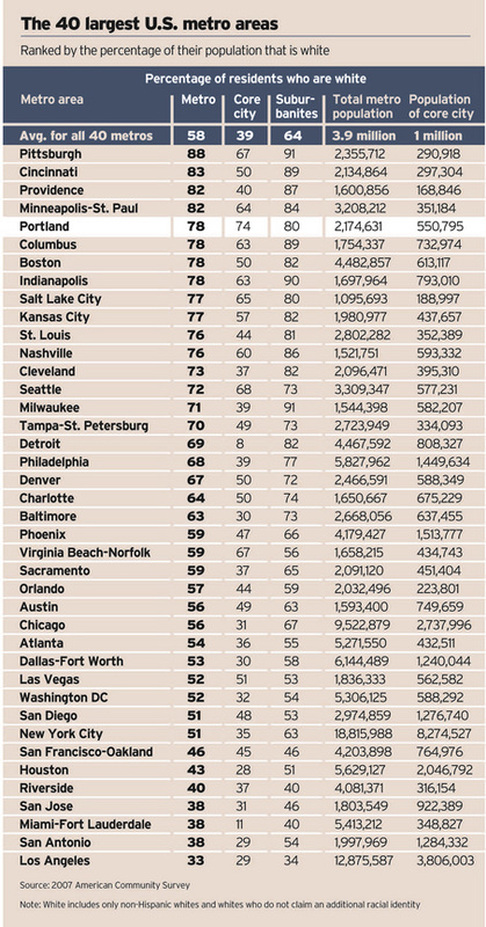

I flew to Portland from San Francisco and upon entering the airplane immediately noted something odd. As far as I could see, there were only Caucasians on the plane. The impression of a relatively homogeneous population was supported by what I saw in the center of the city. It certainly seemed to be a very white city. In fact, Portland's population is 74% white, the highest of any major city in the United States. By comparison, only 45% of San Francisco's population is white. (See core city populations in chart at right.)

As the cities in the United States with the highest livability rankings all tend to have large white (or in the case of Honolulu, Asian) populations, this is a significant point to grasp when struggling to understand America's urban problems and blight. It illustrates the continuing damage America's history of slavery, racism, segregation and unwillingness to effectively deal with social problems has wrought in those cities with large non-white populations. I will write more about this in a subsequent posting.

I came to learn that Portland's relatively few non-white inhabitants (both blacks and Hispanics) have gradually been pushed to the edge of the city, far away from many of the things that make Portland such a livable city, due to gentrification. I stayed in what had previously been an African American neighborhood in NE Portland (Irvington), but today there are relatively few black Americans living there. I became friends with one of my neighbors, Susan, and her good friend Ed, a homeless African American who sometimes sleeps on Susan's porch. They told me about a pervasive, if not overt, racism that exists in this supposedly very progressive town. Ed's life story was probably not atypical for a black American man. From the start he had no advantages and faced multiple hardships. It's amazing to me that he still has an optimistic life view.

Storefronts along Alberta Street in NE Portland.

Storefronts along Alberta Street in NE Portland. It is a strikingly clean city, with innovative street design, excellent public transport, an enviable food scene, and a large population of active bicyclists.

It is also a city of vibrant and lively local neighborhoods. I found its many independent coffee shops to be an excellent indicator of an active and vital community. These local coffee shops provide social and work spaces where people can interact, and these interactions extend out into the sidewalks and streets. They are important social hubs that tie neighborhoods and the city together.

For a city of low diversity, Portland also has an amazing range of ethnic foods and overall a food (and beer) scene considered to be one of the best in the United States.

A moist sidewalk in Portland, surrounded by lush early spring vegetation.

A moist sidewalk in Portland, surrounded by lush early spring vegetation. The vast majority of streets are lined with trees, and there is almost always a planting strip, or green right of way, between the sidewalk and the street that is planted with trees, bushes, flowers and grass. A planted right of way is rather common in American cities. What is not common is the exuberance of vegetation (this is a moist and temperate climate) and the high number of plant species that are grown around houses. As you can see in the picture to the right, this typical Portland street does not show large lawns, but instead a variety of vegetation and high species diversity. This is a city where gardening is taken seriously and front yards are really more like gardens.

See some typical Portland streets scenes below.

Washington Park, above downtown, in NW Portland

Washington Park, above downtown, in NW Portland  A swale in the right of way of this street, helping to control water run off.

A swale in the right of way of this street, helping to control water run off. But there are signs that Portland is trying to do things a bit differently. To the right you can see a picture of a swale, an area designed to absorb rainwater runoff from the street and keep it from overwhelming sewers. You find these all over the city, planted with species that like water.

There are also a variety of curb extensions (often at corners) that make pedestrians more visible to traffic, make street crossing distances shorter, and also slow traffic to improve safety.

Traffic is also slowed in some neighborhoods with features such as speed bumps and mini-roundabouts (often with very nice plantings within).

Below you can see a few pedestrian surfaces that break with the generally bleak cement pedestrian landscape.

Max train running through downtown.

Max train running through downtown. I continued to use Portland's buses and trains on nearly a daily basis. For an American city with a relatively low population density, Portland has rather excellent public transportation. It's not at all unpleasant to use and it's often possible to get to even marginal areas of the city with only one transfer. Buses and trains are clean and well-maintained.

The city's investment in light rail transport has, according to studies, helped the city retain its core population better than cities that didn't create light rail systems. But contrary to my expectations, and despite the obvious huge investments the city and region have made, the percentage of commuters using public transport in Portland has actually decreased over the last 30 years. Cars have become more and more dominant. See research here.

The underlying problem is that driving is still heavily subsidized here as elsewhere in US. Gasoline taxes do not cover the cost of building and maintaining roads. Parking, even when there is a charge, is also usually heavily subsidized. There are few disincentives to drive. This is where Portland and other US cities differ greatly from cities in most other developed nations. American cities make driving far too attractive and hence steer people away from public transport. Some might say that if driving is the preferred form of transport for city dwellers, why not subsidize it? The problem is that car-centric cities are less attractive and healthy places to live. Automobile dependence undermines the development of cities built on a human scale, places that are pedestrian friendly, where walking is easy, and where local community life thrives. It's interesting to note that the most walkable areas of US cities, those areas most similar to older cities in Europe, are generally the most sought after and expensive. What's more, car dependence is unsustainable and is adding to environmental problems, such as air pollution and smog.

Prime riverfront area on east side blighted by overpasses.

Prime riverfront area on east side blighted by overpasses. The problems, as above, often go back to the automobile. The domination of the landscape by automobile infrastructure robs it of human scale, creating many central sectors where pedestrians (and pedestrian associated businesses and features) are rare. Highways bisect the city and create vast zones along their edges that are cut off from areas on the other side. These areas are generally undesirable places to live. Motor vehicle infrastructure also deprives vast areas of the center of development. I saw extensive empty spaces, very centrally located, that could provide land for development. But I don't imagine anyone would want to develop property beneath or adjacent to a highway overpass.

The picture above shows the almost completely lifeless (with the exception of auto traffic) east bank area of Portland. There are virtually no shops, no restaurants, and no housing. There is no reason to come to this place except to pass through by car, although it has some of the best views of downtown Portland. This barren no-mans-land seals the eastern side of the city off from the river and the promenade that runs along it. I find it hard to grasp how anyone envisioned or approved such an incredible destruction of potentially highly valuable space right at the city's core.

You can see more pictures from this area below.

Tell-tale sign of American city: Prime downtown corner, now a lifeless parking lot.

Tell-tale sign of American city: Prime downtown corner, now a lifeless parking lot. Everywhere I went in Portland, I was met with parking lots, whether it be on vacant central city lots, in front of unsightly strip malls, or in immense proportions surrounding malls, office towers or institutions such as hospitals. The parking lots are dead zones in the city, and break up the texture of downtown and other areas. They break the flow of pedestrians walking between businesses. See more examples below.

Elegant residential area's wide paved streets.

Elegant residential area's wide paved streets. I should also mention here that although sidewalks are not allocated a particularly generous amount of space, they are likewise generally covered rather artlessly with a non-permeable frosting of absolutely unadorned cement.

Bicycle infrastructure in Portland.

Bicycle infrastructure in Portland. This will come as a surprise to many bicyclists in Portland, who I think live in a bit of a bubble (without exposure to cities with far better biking infrastructure).

In this city, bicycles generally share the streets with cars, with no marked bicycle lanes on most streets. I am aware that some people believe this state of affairs is actually better and safer. But for children, the elderly, and those not particularly comfortable riding bicycles (like new riders), the major streets are intimidating. In the center of the city and along some main thoroughfares there are rather poorly marked bicycle lanes, but they are incomplete and confusing.

These bike lanes are intimidating for most potential users because they are not well demarcated and not fully separated from traffic. In the downtown area, bicyclists share the crowded city streets with fast-moving traffic. With the incredibly wide streets this city has, why can't dedicated and separated bike lanes be added at least to major thoroughfares? Portland prides itself on being a bike-friendly city, but the enthusiasm for biking is not, as far as I can see, based upon excellent biking infrastructure. There are, certainly, better-than-average bike parking areas and many excellent bike shops. But people here simply love to bike and those who bike a lot are apparently comfortable sharing space with automobiles.

Unpaved street in poor neighborhood with no sidewalks and few street trees.

Unpaved street in poor neighborhood with no sidewalks and few street trees. Many of the policies that make Portland so attractive to many young people (and not only the young) are similar to those of upscale suburbs. Portland's urban growth boundaries and other regulations raise land prices and render housing less affordable, just as large lot zoning and expensive building codes do in some wealthy suburbs.

They both contribute to reducing housing affordability for historically disadvantaged communities, and push these people out of the nicer areas.

Above you can see an unpaved street in the poor, eastern side of Portland. Houses here are small, often in poor condition, and the surrounding infrastructure is dramatically different from the center of the city. There are often no sidewalks, streets are in poor condition even when paved, and there are fewer trees planted along the street.

Street in center with lots of interesting detail.

Street in center with lots of interesting detail. Portland certainly has what it takes to bring it to the top. It has a progressive orientation, wealth, a vibrant street culture in many areas, a mild climate, and beautiful natural surroundings. A few things hold it back. First, Portland is part of the United States and is therefore integrated with a national system that brings about a high level of inequality without adequately addressing the related severe social problems. It also is part of a culture that prioritizes the use of automobiles in urban transport. Most people do not want to use public transport, no matter how good it is.

Catching up with world leaders will not be easy. Portland and other US cities need to make difficult and sometimes initially unpopular choices. A broad vision needs to be developed that leads to policies and plans that maximize the quality of life of the majority of a city's inhabitants. Window dressing of the failed auto-centric model won't do. Fortunately there are excellent examples throughout the world of how cities have reinvented themselves and created a far better urban environment. As social problems seem less severe in Portland than in most large US cities, it has an inherent advantage that it can build upon further.

One area that the city can start on right away is making driving less attractive. As long as driving is the easiest, fastest, and often cheapest option for most of the population, even improved bike lanes and better public transport won't make much of a difference. For starters, drivers should bear the full cost of driving, including its externalities. Subsidies and other incentives for car transport should to be eliminated. Cities should not distort their fabric to provide space for cars. Parking availability should be reduced and parking rates hiked to cover the true cost of providing parking spaces. Congestion pricing should be implemented. Gasoline should be taxed at a level that pays for necessary auto infrastructure. Auto-insurance rates should be linked to how much people actually drive. All of these changes would make a huge difference in how people choose to move around the city. The money saved from eliminating driving subsidies could go into building better public transport, safer and more welcoming bicycling infrastructure, and improved sidewalks. Sadly, these options are probably politically near to impossible in the United States.

American cities are dynamic places in the midst of constant change. Portland is moving in the direction of improved livability and is really a delightful place in so many ways, but there is much more it could do to make great strides forward. Auto dependence, coupled with America's serious social problems, is at the core of the problem. However, if any American city has a chance of climbing up the global rankings, it might just be Portland.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed