|

I've spent two weeks on a friend's little farm high in the mountains of central Norway. Here are a few pics that I hope capture some of the atmosphere of this beautiful place.

1 Comment

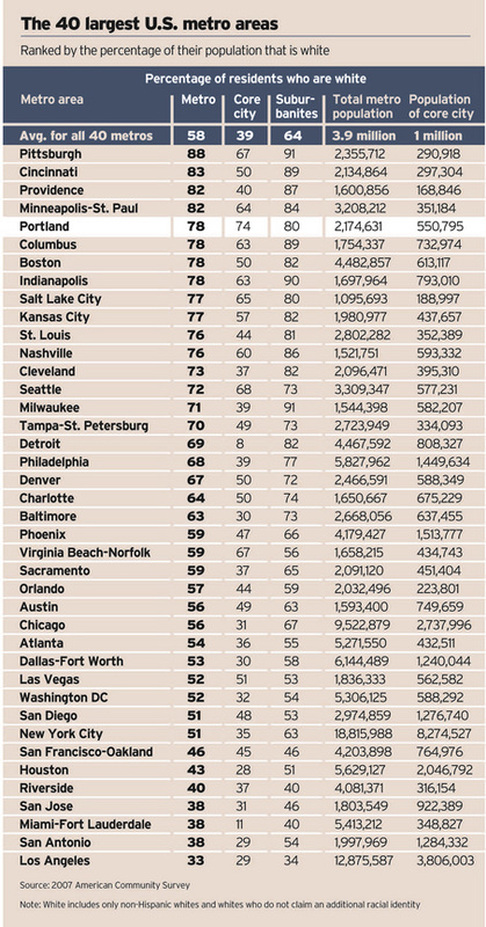

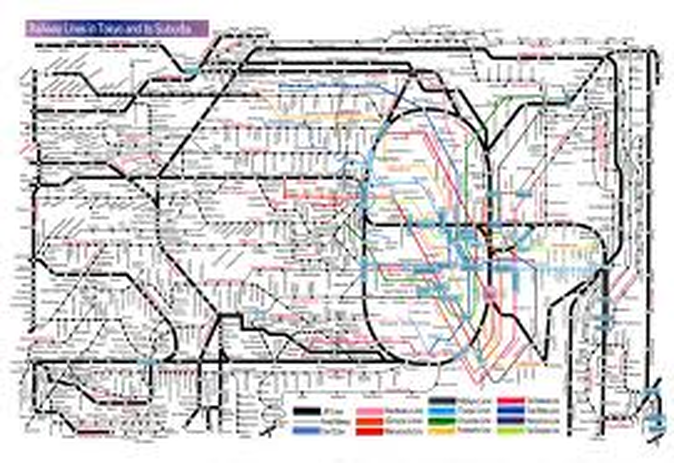

Characteristic Portland house with vegetable garden out front. Characteristic Portland house with vegetable garden out front. I spent the month of March in the lush, green and rather beautiful city of Portland, Oregon. Portland will serve as my entry point into American cities on this trip to the USA. I chose to visit it because of its almost legendary status among urban planners. Soon after arrival I recognized how unique this city is in the United States. Portland capitalizes on its assets in a way that creates a flourishing and very livable city - the best I've seen in any major US city. It offers a vision of what a medium-sized American city can be with the right policies, planning, and execution. It's a world apart from the typical American city, both in its well-designed urban environment and its stunning natural surroundings.  Portland's differences, however, go beyond its great urban design and rich nature. There is a major demographic difference here. I flew to Portland from San Francisco and upon entering the airplane immediately noted something odd. As far as I could see, there were only Caucasians on the plane. The impression of a relatively homogeneous population was supported by what I saw in the center of the city. It certainly seemed to be a very white city. In fact, Portland's population is 74% white, the highest of any major city in the United States. By comparison, only 45% of San Francisco's population is white. (See core city populations in chart at right.) As the cities in the United States with the highest livability rankings all tend to have large white (or in the case of Honolulu, Asian) populations, this is a significant point to grasp when struggling to understand America's urban problems and blight. It illustrates the continuing damage America's history of slavery, racism, segregation and unwillingness to effectively deal with social problems has wrought in those cities with large non-white populations. I will write more about this in a subsequent posting. I came to learn that Portland's relatively few non-white inhabitants (both blacks and Hispanics) have gradually been pushed to the edge of the city, far away from many of the things that make Portland such a livable city, due to gentrification. I stayed in what had previously been an African American neighborhood in NE Portland (Irvington), but today there are relatively few black Americans living there. I became friends with one of my neighbors, Susan, and her good friend Ed, a homeless African American who sometimes sleeps on Susan's porch. They told me about a pervasive, if not overt, racism that exists in this supposedly very progressive town. Ed's life story was probably not atypical for a black American man. From the start he had no advantages and faced multiple hardships. It's amazing to me that he still has an optimistic life view.  Storefronts along Alberta Street in NE Portland. Storefronts along Alberta Street in NE Portland. I felt it important to bring Portland's demographics to the fore because they may help explain its unique character. It is a strikingly clean city, with innovative street design, excellent public transport, an enviable food scene, and a large population of active bicyclists. It is also a city of vibrant and lively local neighborhoods. I found its many independent coffee shops to be an excellent indicator of an active and vital community. These local coffee shops provide social and work spaces where people can interact, and these interactions extend out into the sidewalks and streets. They are important social hubs that tie neighborhoods and the city together. For a city of low diversity, Portland also has an amazing range of ethnic foods and overall a food (and beer) scene considered to be one of the best in the United States.  A moist sidewalk in Portland, surrounded by lush early spring vegetation. A moist sidewalk in Portland, surrounded by lush early spring vegetation. Typical neighborhoods in Portland are impressive, and really seem almost suburban. Beautiful homes are the norm, with large lush gardens surrounding them. In this respect, living standards appear to be very high in Portland, and would vie with those in the richest countries around the world. The vast majority of streets are lined with trees, and there is almost always a planting strip, or green right of way, between the sidewalk and the street that is planted with trees, bushes, flowers and grass. A planted right of way is rather common in American cities. What is not common is the exuberance of vegetation (this is a moist and temperate climate) and the high number of plant species that are grown around houses. As you can see in the picture to the right, this typical Portland street does not show large lawns, but instead a variety of vegetation and high species diversity. This is a city where gardening is taken seriously and front yards are really more like gardens. See some typical Portland streets scenes below.  Washington Park, above downtown, in NW Portland Washington Park, above downtown, in NW Portland In terms of public green space, Portland has among the most public park space per person of any major city in the US. In a recent study, it ranked 5th in the US, after cities such as Raleigh, NC and Lincoln, NE. And even without the public parks, the city's large yards and private green spaces keep you enveloped in green at almost all times. It's hard to get away from it, except in the very core of the city.  A swale in the right of way of this street, helping to control water run off. A swale in the right of way of this street, helping to control water run off. Portland also stands apart in its innovative street design in many areas. Like most American cities, sidewalks here are generally artlessly covered with cement, and streets are often rather roughly covered with asphalt (and are very often in need of repair). But there are signs that Portland is trying to do things a bit differently. To the right you can see a picture of a swale, an area designed to absorb rainwater runoff from the street and keep it from overwhelming sewers. You find these all over the city, planted with species that like water. There are also a variety of curb extensions (often at corners) that make pedestrians more visible to traffic, make street crossing distances shorter, and also slow traffic to improve safety. Traffic is also slowed in some neighborhoods with features such as speed bumps and mini-roundabouts (often with very nice plantings within). Below you can see a few pedestrian surfaces that break with the generally bleak cement pedestrian landscape.  Max train running through downtown. Max train running through downtown. Wherever I go I rely on public transportation (or bicycle or foot) to get around, and immediately upon arrival in Portland, I experienced the seamless transition from the airport terminal to the region's light-rail system. I felt as if I were in a northern European city with the well-designed system quickly and quietly taking me to the center of the city, often through beautifully green neighborhoods. I continued to use Portland's buses and trains on nearly a daily basis. For an American city with a relatively low population density, Portland has rather excellent public transportation. It's not at all unpleasant to use and it's often possible to get to even marginal areas of the city with only one transfer. Buses and trains are clean and well-maintained. The city's investment in light rail transport has, according to studies, helped the city retain its core population better than cities that didn't create light rail systems. But contrary to my expectations, and despite the obvious huge investments the city and region have made, the percentage of commuters using public transport in Portland has actually decreased over the last 30 years. Cars have become more and more dominant. See research here. The underlying problem is that driving is still heavily subsidized here as elsewhere in US. Gasoline taxes do not cover the cost of building and maintaining roads. Parking, even when there is a charge, is also usually heavily subsidized. There are few disincentives to drive. This is where Portland and other US cities differ greatly from cities in most other developed nations. American cities make driving far too attractive and hence steer people away from public transport. Some might say that if driving is the preferred form of transport for city dwellers, why not subsidize it? The problem is that car-centric cities are less attractive and healthy places to live. Automobile dependence undermines the development of cities built on a human scale, places that are pedestrian friendly, where walking is easy, and where local community life thrives. It's interesting to note that the most walkable areas of US cities, those areas most similar to older cities in Europe, are generally the most sought after and expensive. What's more, car dependence is unsustainable and is adding to environmental problems, such as air pollution and smog.  Prime riverfront area on east side blighted by overpasses. Prime riverfront area on east side blighted by overpasses. Portland may have one of the highest livability rankings of any American city, but it still clearly exhibits why US cities lag behind their wealthy counterparts in other parts of the world. The problem is inconsistency and unevenness. The city's fantastic attributes are often not nicely tied together and some areas and some details are jarringly unattractive. The problems, as above, often go back to the automobile. The domination of the landscape by automobile infrastructure robs it of human scale, creating many central sectors where pedestrians (and pedestrian associated businesses and features) are rare. Highways bisect the city and create vast zones along their edges that are cut off from areas on the other side. These areas are generally undesirable places to live. Motor vehicle infrastructure also deprives vast areas of the center of development. I saw extensive empty spaces, very centrally located, that could provide land for development. But I don't imagine anyone would want to develop property beneath or adjacent to a highway overpass. The picture above shows the almost completely lifeless (with the exception of auto traffic) east bank area of Portland. There are virtually no shops, no restaurants, and no housing. There is no reason to come to this place except to pass through by car, although it has some of the best views of downtown Portland. This barren no-mans-land seals the eastern side of the city off from the river and the promenade that runs along it. I find it hard to grasp how anyone envisioned or approved such an incredible destruction of potentially highly valuable space right at the city's core. You can see more pictures from this area below.  Tell-tale sign of American city: Prime downtown corner, now a lifeless parking lot. Tell-tale sign of American city: Prime downtown corner, now a lifeless parking lot. Another telltale sign of the American city is the ubiquitous parking lots on vacant land in city centers and surrounding shopping centers and other businesses and institutions. Prime downtown areas of most American cities, including Portland, have barren parking lots, even on corners of major intersections as in the picture at the left. Everywhere I went in Portland, I was met with parking lots, whether it be on vacant central city lots, in front of unsightly strip malls, or in immense proportions surrounding malls, office towers or institutions such as hospitals. The parking lots are dead zones in the city, and break up the texture of downtown and other areas. They break the flow of pedestrians walking between businesses. See more examples below. Portland, I should mention, has made one significant improvement to parking lot blight. In certain central city areas, these parking lots are surrounded by the city's excellent food carts. These food carts bring life and vibrancy back to these areas.  Elegant residential area's wide paved streets. Elegant residential area's wide paved streets. Another thing that catches my attention (and probably anyone coming from Europe or East Asia) would be the extraordinarily broad areas smothered, really, with a coat of asphalt. Streets in Portland are incredibly wide, and vast areas, particularly at intersections, are large enough to house sizable sporting facilities such as tennis or basketball courts. There is a huge amount of not only wasted, but possibly permanently destroyed land, in this city. Once again, the desire to give a majority of the city's public space to automobiles brings unappealing results. The vastness of these streets takes away charm from neighborhoods, encourages cars to drive faster, and in hot sunny weather, must create a strong heat-island effect. You can see some examples of Portland's remarkably wide streets below. I should also mention here that although sidewalks are not allocated a particularly generous amount of space, they are likewise generally covered rather artlessly with a non-permeable frosting of absolutely unadorned cement.  Bicycle infrastructure in Portland. Bicycle infrastructure in Portland. Portland is renowned in the United States as a kind of bicyclist's paradise. Having lived in the Netherlands, Germany and Japan, I found the bicycle infrastructure, like much else in the city, not up to the highest international standards. In fact, I believe that riding a bicycle in Portland can often be quite intimidating. This will come as a surprise to many bicyclists in Portland, who I think live in a bit of a bubble (without exposure to cities with far better biking infrastructure). In this city, bicycles generally share the streets with cars, with no marked bicycle lanes on most streets. I am aware that some people believe this state of affairs is actually better and safer. But for children, the elderly, and those not particularly comfortable riding bicycles (like new riders), the major streets are intimidating. In the center of the city and along some main thoroughfares there are rather poorly marked bicycle lanes, but they are incomplete and confusing. These bike lanes are intimidating for most potential users because they are not well demarcated and not fully separated from traffic. In the downtown area, bicyclists share the crowded city streets with fast-moving traffic. With the incredibly wide streets this city has, why can't dedicated and separated bike lanes be added at least to major thoroughfares? Portland prides itself on being a bike-friendly city, but the enthusiasm for biking is not, as far as I can see, based upon excellent biking infrastructure. There are, certainly, better-than-average bike parking areas and many excellent bike shops. But people here simply love to bike and those who bike a lot are apparently comfortable sharing space with automobiles.  Unpaved street in poor neighborhood with no sidewalks and few street trees. Unpaved street in poor neighborhood with no sidewalks and few street trees. I normally write about the green divide wherever I go. Portland is no exception in having a green divide and the divide here is driven by the same factors as it is throughout the country. Many of the policies that make Portland so attractive to many young people (and not only the young) are similar to those of upscale suburbs. Portland's urban growth boundaries and other regulations raise land prices and render housing less affordable, just as large lot zoning and expensive building codes do in some wealthy suburbs. They both contribute to reducing housing affordability for historically disadvantaged communities, and push these people out of the nicer areas. Above you can see an unpaved street in the poor, eastern side of Portland. Houses here are small, often in poor condition, and the surrounding infrastructure is dramatically different from the center of the city. There are often no sidewalks, streets are in poor condition even when paved, and there are fewer trees planted along the street.  Street in center with lots of interesting detail. Street in center with lots of interesting detail. Despite its status as a leader in urban design and livability in the USA and the obvious investments in improved transport and infrastructure, Portland is still far from a Sydney or Zurich, two examples of beautifully integrated cities with very highly ranked livability. Portland certainly has what it takes to bring it to the top. It has a progressive orientation, wealth, a vibrant street culture in many areas, a mild climate, and beautiful natural surroundings. A few things hold it back. First, Portland is part of the United States and is therefore integrated with a national system that brings about a high level of inequality without adequately addressing the related severe social problems. It also is part of a culture that prioritizes the use of automobiles in urban transport. Most people do not want to use public transport, no matter how good it is. Catching up with world leaders will not be easy. Portland and other US cities need to make difficult and sometimes initially unpopular choices. A broad vision needs to be developed that leads to policies and plans that maximize the quality of life of the majority of a city's inhabitants. Window dressing of the failed auto-centric model won't do. Fortunately there are excellent examples throughout the world of how cities have reinvented themselves and created a far better urban environment. As social problems seem less severe in Portland than in most large US cities, it has an inherent advantage that it can build upon further. One area that the city can start on right away is making driving less attractive. As long as driving is the easiest, fastest, and often cheapest option for most of the population, even improved bike lanes and better public transport won't make much of a difference. For starters, drivers should bear the full cost of driving, including its externalities. Subsidies and other incentives for car transport should to be eliminated. Cities should not distort their fabric to provide space for cars. Parking availability should be reduced and parking rates hiked to cover the true cost of providing parking spaces. Congestion pricing should be implemented. Gasoline should be taxed at a level that pays for necessary auto infrastructure. Auto-insurance rates should be linked to how much people actually drive. All of these changes would make a huge difference in how people choose to move around the city. The money saved from eliminating driving subsidies could go into building better public transport, safer and more welcoming bicycling infrastructure, and improved sidewalks. Sadly, these options are probably politically near to impossible in the United States. American cities are dynamic places in the midst of constant change. Portland is moving in the direction of improved livability and is really a delightful place in so many ways, but there is much more it could do to make great strides forward. Auto dependence, coupled with America's serious social problems, is at the core of the problem. However, if any American city has a chance of climbing up the global rankings, it might just be Portland.  Building with tiny footprint and artsy wall texture in Ikejiri-Ohashi, crisscrossed by utility wires. Building with tiny footprint and artsy wall texture in Ikejiri-Ohashi, crisscrossed by utility wires. Tokyo is arguably the greatest city in the world. It is certainly the biggest and is a world leader in things ranging from safety (safer than Zurich) to the number of Michelin 3 star restaurants (more than Paris). What makes Tokyo so tantalizing to me is its unrivaled density of alluring features and its profusion of things to do and see. The very structure of Tokyo is based upon adeptly and intensively utilizing every square meter of available space. This intensity, flavored with Japanese culture, is the alchemy that creates this city's good life. The beauty of Tokyo is not the sort of beauty people associate with cities such as Paris. Paris and Tokyo do have certain things in common, including incredible food, high culture, and general sophistication. But Tokyo's beauty is not visible on a grand scale. Instead it resides in the small details of every street.  Street scene at night from Shibuya (courtesy cocoip) Street scene at night from Shibuya (courtesy cocoip) These details are evident on every street you walk along. But in Tokyo's main shopping and entertainment districts, the density of detail is like nothing you will see anywhere else. The picture to the right shows a street in Shibuya, with signs advertising fast food, convenience stores, restaurants, karaoke boxes and pachinko parlors among many other businesses. It's a kind of madness that plays out on multiple levels in all the multi-storied buildings. It's quite normal to go up 6 floors to visit your favorite bar. The strangeness to most foreigners of the written Japanese language makes Tokyo appear even madder than it is. But reading the language is like turning on the lights! There is so much information.  Drug store in central Tokyo. Drug store in central Tokyo. The intensity of details and features is not skin deep. It penetrates into most any business you enter. You can see it in the tightly-packed 24-hour convenience stores that are everywhere. They are brimming with products and services often unlike those in any other country, with astounding variety, including prepared Japanese foods, an enormous variety of beverages, and a broad selection of groceries and toiletries. While living in Japan for 10 years, I was always disappointed to come home and see the relatively barren, often dirty, 7-11 stores in the US. I wondered how they could afford to utilize their retail space so poorly. Drug stores are equally full of density and surprises. The picture above shows Matsumoto Kiyoshi, one of my favorites, in Yurakucho (near Tokyo Station). I don't believe you can find intense organization and variety like this in any store outside of Japan. Shelves and all available spaces, literally, are carefully and artfully filled with seemingly unending products. This product variety, I believe, is partly due to Japan having a dualistic medical system based on both Western medicine and traditional Japanese medicine (similar to Chinese medicine). I wonder if product developers from the US and Europe come to Japan for new product ideas. The stores are full of them!  An incredible selection of insoles to insert in shoes, at Tokyu Hands. An incredible selection of insoles to insert in shoes, at Tokyu Hands. The retail abundance in convenience and drug stores is not an anomaly. The remarkable cornucopia extends into many other types of businesses, from bountiful bookstores to exhaustively stocked do-it-yourself stores such as the eight-story-tall Tokyu Hands in Shibuya,. pictured at the right. In my opinion, it's difficult to find retail rivaling Japan's abroad, at least when it comes to the variety and quality of products offered. I'm interested in Japan's hyper-developed retail spaces because, like Japanese cooking (which I wrote about in my last posting), they help provide a kind of framework for understanding the uniqueness of Tokyo and other Japanese cities. They're a window into Japanese culture that showcase characteristics that permeate and define Tokyo's general physical environment and urban infrastructure.  Aerial view of the Ohashi Junction project. Aerial view of the Ohashi Junction project. A striking example of the Japanese approach to urban design is Ohashi Junction in Ikejiri-Ohashi. This traffic management project includes a new covered highway interchange enmeshed in a complex of apartment buildings, retail outlets, a public library, a soccer field and a 'rooftop' park (including a rice paddy) extending along the cover of the circular junction (see the picture to the right). This project exemplifies the detail-oriented, space intensive, innovative design that makes Tokyo unique. As this massive project was only minutes from where I stayed in Ikejiri-Ohashi, I had plenty of time to explore the details. As you can see in the pictures below, very little space went to waste and high quality materials were used throughout. I marveled at the pristine and seemingly perfect cement used throughout the structure. If a project of this quality, complexity and innovativeness were to arise in New York or London, it would be world famous. Nowhere else have I seen highway infrastructure so fully and tastefully integrated into the urban fabric that it actually improves a neighborhood. I took the elevator up to the Meguro Sky Garden above the interchange and ventured out into the lush landscaping high above the streets of Tokyo. It was hard to imagine that I was walking on the roof of a highway junction. The park space was comfortable, with plenty of places to sit and enjoy the view. It was remarkable and a true green oasis in what would normally be a wasteland used only by vehicles. If you want to see what it's like to drive through the interchange and then further along a covered highway emerging in another part of Tokyo, check out this video. Below are a few pictures I took on my walk around the project.  Stream and diverse vegetation on the Meguro Green Promenade. Stream and diverse vegetation on the Meguro Green Promenade. Almost directly across the street from the Ohashi Junction project is the entrance to the Meguro Green Promenade, another example of unusual design and evidence of the surprising complexity and diversity of Tokyo. I was in Ikejiri-Ohashi because the friends I stayed with live here, and I just happened to discover these things within five minutes of their home. The Green Promenade runs for several kilometers along the surface of a covered portion of the Meguro River and has been designed as a peaceful oasis in the middle of this hectic city. It is filled with biodiversity and features a little stream with crystal-clear water which provides a home for small fish, crayfish and water striders. The surrounding landscaping is atypical, especially for Tokyo, in that it has a high level of plant, insect and animal biodiversity. Although I was in the center of the biggest city in the world, I saw many birds, butterflies and other insect life. This totally artificial creation has become an important refuge for nature. In the video below, you can walk with me along the Promenade. I need to improve my video-taking technique, but it's a glimpse into another part of Tokyo few visitors see.  Sign for Machi-ing Hongo, which works to maintain and green the neighborhood Sign for Machi-ing Hongo, which works to maintain and green the neighborhood One day I went to visit my old central-Tokyo neighborhood of Bunkyo Ward (where I lived for 10 years), and was pleased to see the evidence of citizen involvement in maintaining the urban environment. The sign to the right is from a local non-profit in the Hongo neighborhood. The organization works to keep the streets clean and green. This NPO (non-profit organization) is called something like "Towning Hongo" if translated into English. This sign illustrates the flexibility and acquisitiveness of the Japanese language. Japanese unabashedly appropriates words, acronyms and even grammatical phrases from foreign languages with no fear of diluting itself. The Japanese may at times be a bit xenophobic, but their language isn't. The top line of the sign reads "NPO Corporation 'Machi-ing' Hongo. New citizen-based movements are taking to the streets as a reaction to poor economic conditions, lower government resources and a shift away from small, private businesses to chain stores and restaurants. The locally owned stores were apparently better neighborhood stewards.  My friend Sachiko on the platform waiting for our train to Tochigi Prefecture. My friend Sachiko on the platform waiting for our train to Tochigi Prefecture. Finally, a word on transport. Tokyo has by far the most comprehensive and complex public transportation network in the world. It is as dense and complex as everything else in this city but makes getting around very easy and stress-free (except, perhaps, during rush hour). Tokyoites tend to take public transport, walk or ride their bicycles instead of driving cars. This city is also connected with all other major cities in Japan by the world-famous bullet train system (picture at left). The stations and trains are spotless and trains are almost always perfectly on time. Below is a map of the full Tokyo metropolitan commuter rail network, including subways and the many other private rail lines Tokyoites use to get around their metro area. There are over 1000 stations. No system anywhere else comes close in scale.  A breathtaking approach to Manhattan, along the East River in Astoria in Queens. A breathtaking approach to Manhattan, along the East River in Astoria in Queens. After more than nearly 4 years away, last summer I came back for a long visit to a greener and better New York. Not only are many of the city's neighborhoods gaining a higher quality of life, but the city seems to be finally taking advantage of one of its greatest assets: water on all sides. New York is an archipelago, just like Stockholm or Hong Kong, yet pedestrian access to its waterfront has been rather limited for decades and often the wet edges have been far from glamorous. Things are changing.  World-class quality: Washington Square Park after its recent renovation. World-class quality: Washington Square Park after its recent renovation. I lived in New York City for 8 years, and had my first CitiNature project here in 2002. At that time the city was starting some exciting projects. Central Park was already beautifully restored, the Hudson River Park was under construction, beginning a total transformation of Manhattan's West Side, and the High Line park was conceived. But in so many ways at that time, the city was far behind its peers around the world in the quality of its infrastructure and waterfront development. Every time I would go to cities such as London, Sydney or Singapore I would feel let down, asking myself, 'If they can do it, why can't we?' And biking in New York was hazardous. I have always been a bike commuter, but riding my bike from the Upper West Side of Manhattan, where I lived, to any other part of the city was plain and simply dangerous.  Bike path in Long Island City, Queens, right off the Queensboro Bridge bicycle path. Bike path in Long Island City, Queens, right off the Queensboro Bridge bicycle path. This last summer, I recognized that a process of fundamental change was underway. The city was becoming a serious global contender in green design and sustainability and moving towards a higher quality of urban life. In parts of Brooklyn I could have mistaken myself for being in Amsterdam or Dusseldorf. In Manhattan new bicycle lanes, separated from traffic, were being built on many Avenues and it was now a pleasure (and safe) to ride my bike over large tracts of the city. I could ride from E 45th Street, where I was staying, to the Bowery in 15 minutes - faster than using any form of public transport. I could also ride from the East Side of Manhattan to Queens, over the Queensboro Bridge, in about 10 minutes. The city was now bike friendly, although work is still underway to fill critical gaps in the network.  Bike path on the Williamsburg Bridge, connecting Manhattan to Brooklyn. Bike path on the Williamsburg Bridge, connecting Manhattan to Brooklyn. I believe that New York is on its way to becoming one of the great biking cities of the world. In my 2 months in New York during the summer, I discovered how easy it is to move around inside the boroughs and between them, as well. There are 4 bridges with bike paths over the East River, connecting Manhattan to Queens and Brooklyn. Throughout the city there are nearly 400 miles of bike paths and the network is becoming denser. New York is no Amsterdam in terms of bike infrastructure density, but it is becoming easier and easier to get around this city solely by bicycle. Recent news, however, indicates that this progress may be under threat. Possible successors to Mayor Bloomberg are less bike friendly and have threatened cutbacks in bike lane construction.  A soccer pitch in a park on Roosevelt Island, with a view of Manhattan. A soccer pitch in a park on Roosevelt Island, with a view of Manhattan. In addition to massively expanded bicycle infrastructure, I discovered park renovations going on throughout the city. Formerly neglected parks in all boroughs are getting attention, making their neighborhoods more inviting places. People are responding and in any newly created or renovated park I saw, there were lots of people walking, picnicking, rollerblading, biking, sunbathing and of course, just relaxing. Poorly maintained parks were clearly not as popular and often almost empty I think it should be obvious to anyone living in New York that quality green space is in short supply and there is strong public demand for it.  Corroding iron fence, sadly typical of waterfront infrastructure in much of New York. Corroding iron fence, sadly typical of waterfront infrastructure in much of New York. Although New York has made considerable progress in the last decade, a tour along the shoreline can be discouraging. Large portions of the waterfront are still inaccessible and where it is open to the public, it is often in embarrassingly derelict condition. By bicycle and on foot, I explored the entire shoreline of Manhattan, the full perimeter of Roosevelt Island, and the sides of Queens and Brooklyn facing Manhattan. In contrast to the stunning Hudson River Park, most pedestrian waterfront areas of the city are in a crumbling state of disrepair. Pavements are sinking and uneven, access is difficult for nearby residents (most glaringly, along the west side of Harlem), fences are corroding and falling into the rivers, and parks along the water are poorly maintained and litter-strewn, Most readers of this blog, who live in the wealthier parts of the city, may be surprised to read this as parks in their neighborhoods are usually well maintained. It certainly seems that there is a divide between wealthier and poorer neighborhoods in terms of park investment and maintenance.  New park on the waterfront in Long Island City, Queens. New park on the waterfront in Long Island City, Queens. To be fair, the city has its work cut out for it. Decades of underinvestment have left the present administration saddled with an unending list of urgent projects. But the task of rehabilitating the city's shoreline, and opening it to pedestrians, is . underway. There are large scale projects planned such as rehabilitating, expanding and extending parks along the east side of Manhattan and building the Queens East River and North Shore Greenway. There are numerous smaller projects, often associated with new development along the formerly industrial riverfront in Queens and Brooklyn. The plan is to have these parks one day connected in a continuous sweep of green spaces and recreational facilities along the entire perimeter of all the islands within the city.  Carl Schurz Park, on the Upper East Side along the East River, nearing final restoration. Carl Schurz Park, on the Upper East Side along the East River, nearing final restoration. New York is without question one of the most interesting and dynamic cities in the world. Few places can compare with its mind-boggling array of cultural, culinary, educational (and so many other) offerings. But one place where New York has suffered in comparison to cities with the highest quality of life, according to various measures, is public infrastructure. While arguably having the best metro system in the United States, and one of the few systems I know of that operates 24 hours a day, it is run down and rather dirty in most stations. Public pedestrian infrastructure, likewise, does not compare well. Sidewalks are typically of artless, poured cement, streets are often roughly paved, and green spaces (especially outside of the wealthier parts of Manhattan and Brooklyn) are not up to standard. But the future looks bright. The scale of change I've witnessed tells me that New York is at last serious about catching up and becoming a truly world-class city in terms of the physical environment it provides. This is great news for the millions of people who call New York home. |

about the authorCategories

All

Archives

October 2017

After nearly two decades of corporate duty, I decided to follow my heart and do what I love: make cities greener and healthier places. Over the coming years I will be traveling to cities all over the world, reporting on what I see and learning about how even resource-poor places can improve urban lives through urban greening and greener lifestyles. I've started the CitiNature project to channel my energies and drive initiatives supporting equal access to green amenities for everyone.

|

| a better urban life |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed