Mother and daughter walk on Tarasivska Street

Mother and daughter walk on Tarasivska Street Although I made it to the USSR way back in 1984, Kiev and the Ukraine had to wait until this summer. There was a particularly high level of anticipation, as the idea of "Kiev" had always captivated me. I just somehow knew it would be fascinating. I'd read books dealing with Ukraine's rather difficult history, as well as contemporary accounts that weren't particularly complimentary (one describing Ukraine as "the Africa of Europe"). What's more, this is a country in the midst of a civil war. But I'd also read lots of positive travel accounts and few things attract me more than underrated and under-visited cities and countries.

Arrival brought me into a not totally unfamiliar world. Maybe the closest parallel in my recent experience would be Belgrade, Serbia. Ukraine may be undergoing very hard times but Kiev, at least, is a pleasant place. One simple way of describing my first impression upon arrival here would be: "it's better than I expected." Average income levels might suggest that Kiev would look as poor as cities in Central America or even Africa. On the surface at least, Kiev was nothing like cities in those regions. And although Kiev is familiarly European in character, it is European in the eastern sense. Structurally and atmospherically it's very much as I remember parts of St. Petersburg back in 1984 (when it was still called Leningrad) and Moscow in 1991. The bulk of this city is obviously a product of Soviet urban planning - which in theory is itself not radically different from planning decades ago in northern European cities (especially Helsinki). But from my hotel window on the edge of the city where I stayed the first night, there were also tantalizing glimpses of something else: little houses with gardens on narrow lanes, with a general sense of dereliction, much as can be found in parts of American cities and towns. Maybe that's also part of the familiarity I experienced.

I could imagine the important political and ideological statement the redesigned and rebuilt center made. it's a vision of the triumphal Soviet Union, Stalin's vision of Soviet power. This whole area has wide avenues and large buildings built in the style sometimes called "Stalin baroque." The monumental scale is impressive, but it's not particularly inviting. The dozens of little kiosks and cafes that have popped up, however, add a nice human scale and detail to the streetscape, and give good reason to loiter and people watch. .But still, the more cozy streets lie elsewhere, in other, older parts of the city. A thought that struck me was the scarce resources that must have been put into this area at a time when the country was still reeling from the devastation of the war. Living standards at this time were terribly low. As important as it may have been to morale after the war, the diversion of resources to build this showcase center must have held back the building of desperately needed housing.

The pictures I have give such a poor impression that I recommend going to Google Street View to get a sense of what this and other streets in Kiev are like. Click HERE to take a peek at Khreshchatyk Street.

Besarabsky Square (Street View and picture above), at the end of Khreshchatyk Street, give a perfect example of how richly beautiful this city can be. The old Besarabsky Market, built around 1910 (the building at the back left of the photo), is itself is a lively center for fresh foods, and also lots of little restaurants, including Vietnamese and Vegan. I don't know how much damage this area suffered during the war, but somehow it seems to be basically intact (or rebuilt).

Below is a sampling of pre-war architecture that dominates much of the center.

There are many historic areas with monasteries and churches, mostly along the high west bank of the Dnieper. This river, by the way, is a defining feature of Kiev. It divides the city in two, and from the hills on the west bank, there are scenic views over the river as it winds through the city. Along the edges are promenades with cafes, the historic Podil district, and in the middle of the river, Hydropark, an island with beaches. It fascinated me to learn that the Dnieper has a system of locks that allow rather large ships to come to Kiev from the Black Sea and beyond. It is a real port city, despite being more than 800km from the sea.

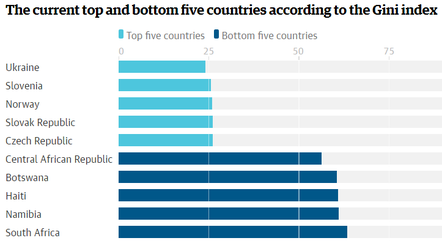

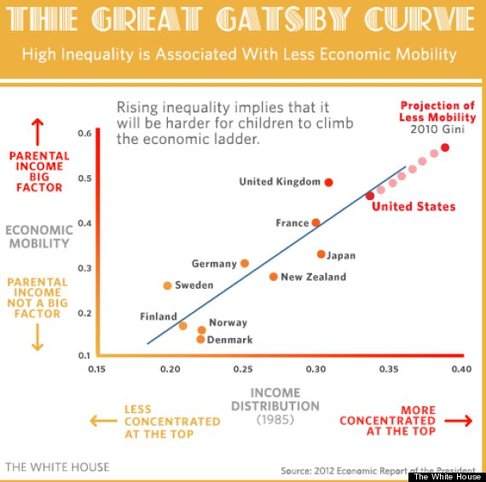

2017, The Guardian

2017, The Guardian According to the IMF, Ukraine's average income (adjusted for purchasing power) is between that of El Salvador and Belize, and near that of Honduras. Once again, as I've noticed so often, countries with low GINI coefficients (and low inequality) look much better than those with high GINI coefficients, even those with far higher incomes. I always look at this imperfect measure as I visit new countries because it often helps explain what I'm seeing on the ground. Ukraine has one of the lowest GINI coefficients on the planet, and this can go a long way to explaining how orderly and decent Kiev is compared to other cities in countries at a similar GDP level. But there is something else at work here in Kiev, as well. Maybe it's the legacy of being part of an industrialized world power with intellectual capital and the resources to build things like a metro system, a well-planned urban structure, and the institutions we associate with a developed country. But then again, that may be a kind of "Kiev mirage": the superficial appearance of a high level of development, even if things are very rough around the edges. Maybe if you scratch below the surface, things are really as bad as the numbers indicate. I found signs of this when I visited crumbling hospitals and the dilapidated Kiev Zoo.

But on the whole, Kiev is somehow not really the developing world, in the sense that many African or Latin American cities are. To me, it's just a rather rundown version of Europe. Poverty certainly exists here on a wide scale, but it takes a different form in it's spatial and structural expression. A fine example of this would be the generous allocation of green space throughout the city. This is not something you find in most poor cities.

The kiosk phenomenon is widespread, and there are kiosks selling all sorts of foods, and pretty much anything....from hardware to clothing. Along with the coffee kiosks, most streets have food kiosks as well, selling savory and sweet pastries. The most vibrant and busy areas are around metro stops. Here there is always a buzz of activity, with all sorts of kiosks and vendors. The underground passageways of the metro entrances are also lined with all sorts of stores. I seemed to notice a lot of flower shops and clothing vendors. Urban planners complain about all these kiosks, many of which have risen illegally or with bribes, but I found them a lively addition to what might otherwise be rather lifeless streets.

Below, a sampling of coffee kiosks, including one named after Obama.

Entrance to Universytet Metro Station

Entrance to Universytet Metro Station *

One word about the language and alphabet. I imagine many would-be visitors to Ukraine are intimidated by the lack of English and the strange looking alphabet. In fact, the Cyrillic alphabet is extremely easy to learn (just an hour or so can get you functionally reading place names), and I relied steadily on the little public transportation guide in the picture on the left, which listed all the hundreds of bus, tram and metro lines. It allowed me to take advantage of the comprehensive and generally excellent transport system.

One of my favorite spots in Kiev, really a magical place, is the main train station (Tsentralnyy Vokzal), a building that survived the war and has a real grandeur to it (see two photos below). It's exciting that in Ukraine trains are still the main way to get around the country, and the station was busy and energetic. I loved spending time there. It's one of my observations: rich countries are highly organized and honestly, kind of boring. I didn't have that feeling at all in Kiev. So much action, so much variety, so many interesting characters.

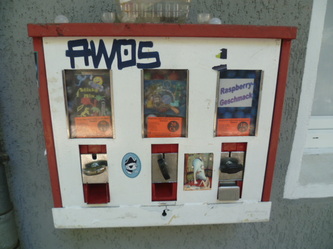

Soviet beverage vending machine from decades ago

Soviet beverage vending machine from decades ago Arriving in the Soviet Union as an American was an unusual thing, and the experience was profoundly different from any I'd had before. The most mundane aspects of daily life were strange to me. I remember the beverage vending machines (example above) where glasses were used and reused without washing (I think you could rinse the glasses); the ice cream vendors selling delicious vanilla ice cream and raspberry sherbet; the very shabby and practically empty food markets.

There are a couple of interesting books that describe the special products and designs of Soviet life: Made in Russia: Unsung Icons of Soviet Life and Designed in the USSR: 1950-1989

As we were on a Sputnik tour, all aspects of the trip were controlled, and the overarching theme of every day was 'war memorials'. It wasn't hard to imagine why this was so important to people in the Soviet Union (I had a remote inkling of what they'd gone through), but after a few days of getting on tour buses and seeing yet another beautiful but for me boring park commemorating some aspect of the war, I was ready for escape. My buddy and I decided to bail out, and we claimed to be sick one morning, and then headed out on our own. That's when the real adventure began and glimpses of real Soviet life began. I'll save those stories for another time and place.

Kiev, like St. Petersburg, is filled to this day with many memorials of the "Great War". I'm not much of a fan of these things, but some of them in Kiev are really impressive, such as the Motherland Monument (see picture below), and the war museum itself was very engaging and really almost an emotional experience.

Housing in Kiev is dominated by

Panelny Dom buildings, panel-construction buildings, which were the Soviet Union's answer to an acute housing shortage. This was a huge experiment in industrialized housing construction, and on some measures it was a success. These buildings, also called Khrushyovka buildings (as mass construction began during the Kruschev era), appear in large numbers in every ex-Soviet city I've visited. For many people it was their first experience of having a private home, with their own kitchen and bathroom.

While the exteriors and even public hallways look derelict and dilapidated, the inside of apartments can be quite cozy and well maintained. Investment in maintaining public spaces, it seems, is a low priority. The same applies to the yards of buildings. As I wrote above, poverty in Kiev is not evident as it would be in Latin America, where poor neighborhoods take on a radically different structural form. It's evident, instead, perhaps in the level of maintenance. And even here, I'm not sure this is a clear measure, as I've pointed out that apartments in these run down buildings can be quite nice. I really wonder about the condition of things like water pipes, electricity supplies, and heating. The three apartments I stayed in in Kiev varied in quality, but all had good water pressure and no electrical problems. Maybe more revealing, however, is what often lurks behind these apartment blocks. I noticed sadly derelict green spaces, rotting garbage piled high in dumpsters. old cars, and crumbling asphalt.

I was fascinated by vestiges of the Soviet period, such as the elevators in one of the buildings I stayed in (pictured below), still running decades after being installed. I wondered how safe it was, but it sure did work fine. The green paint of the stairwells also was somehow reminiscent of the Soviet past. Why would anyone choose such a color?There is a whole genre of Soviet films that focuses on these sorts of buildings.

What's striking to me is that the physical structure of the streets and green spaces is much like it would be in northern Europe...not so different from developments built in Helsinki in the 1960s and 70s, in fact. The difference is maintenance and upkeep (and no doubt original construction quality). In Kiev, there is only the occasional tended flower bed (emphasis on occasional). The fact that stores (things like little supermarkets and pharmacies) are integrated into the street fronts, and that the streets in these areas are often lined with informal vegetable and fruit stands, brings life to these areas. This is totally different from what you find in lifeless Nordic developments of a similar type, as spotlessly clean as they might be.

Photo: Yevgen Nikiforov

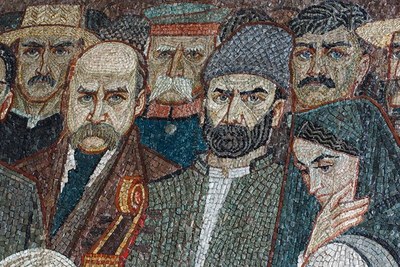

Photo: Yevgen Nikiforov Mosaics from the Soviet period, I've read, often depict an idealized, futuristic vision of Soviet life. My extraordinarily poor camera skills really don't capture how beautiful these things are (I took many pictures but they just don't come through clearly here), so I share examples from two photographers, who have given me permission. The picture above is of row of apartment blocks with large mosaics along Peremohy Prospekt, I passed this place every day while I stayed in an apartment near the derelict Kiev Zoo.

The first picture below is from the Central Bus Station in Kiev, which has a lot of other mosaics. The following site curates pictures of Soviet mosaics in Ukraine: https://sovietmosaicsinukraine.org/en/mosaic/63

The second picture is from the Shevchenko Cinema in Kiev. Read about it here: https://www.wired.com/story/soviet-murals-ukraine/ and check out Yevgen Nikiforov's book "Decommunized: Ukrainian Soviet Mosaics".

The one in the picture here, the ATB-Market next to one of the buildings I stayed in, is the largest chain in Kiev

"STREET FOOD"

"STREET FOOD" There's a chain of cafeteria-style restaurants called Puzata Hata where you have a tray and then just point or grab (if you don't speak Ukrainian or Russian) at whatever it is that looks good as you pass the various counters. The first picture below is of a meal from Puzata Hata, including breaded chicken and a salad, that probably cost about $4, including the drink.

The second picture is from Varenychna Katyusha, another chain which specializes in traditional Ukrainina cuisine. It's also rather inexpensive and good for at least one try. It also has menus with pictures. In the second picture below I have kasha, peas, and some kind of cold soup...I think it was cucumber.

In a big city like Kiev, this is just the tip of the iceberg of inexpensive but generally tasty food. There are countless stands selling all sorts of things from pizza to savory pastries. There are also many mid-range and expensive restaurants, generally with foreign cuisine. I even went to a Turkish restaurants one night.

But as I was staying in rented apartments, I often went shopping and cooked at home to get a feel for that experience, as well.

The picture you see to the left is the view from my hotel window. It was a really nice introduction to Kiev, and I must say this neighborhood (which I later discovered was quite typical of the outskirts of the city) was very attractive its own way. The often ramshackle small houses and poorly paved lanes have a real charm and coziness, as they are all rather unique and generally surrounded by flower and vegetable gardens. Pictures of some of these lanes below.

This was a taste of what will come on my next trips to Ukraine...to get to the small towns and countryside that show a totally different side of this country.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed