― Edward T. Hall, The Silent Language

Houses along bicycle path nestled in green surroundings in the north of Helsinki.

Houses along bicycle path nestled in green surroundings in the north of Helsinki. The good life that Helsinki offers may not be immediately apparent to the short-term visitor. This Baltic city is not a cosmopolitan center brimming with dazzling shopping, a vibrant food scene, or a pulsating nightlife. Instead it's a rather homogeneous, predictable place where the everyday is given priority over the spectacle. In fact, tourists here have often told me that they find the city boring, and boring it may be if you are looking for big-city life of the sort on offer in Paris, London or New York.

The beauty of Helsinki is found in the ordinary, in its steady attention to the banal underpinnings of a secure, pleasant and healthy urban environment. My time here convinced me that it delivers an exceptional quality of life, across many measures, for the majority of its inhabitants. It's not surprising that Helsinki typically ranks among the top ten cities in the world for quality of life. This quality of life is based upon factors such as safety, state of its infrastructure, access to nature, and quality of education and health care. It results from a high level of what I call urban organizational competence (the level and sophistication of a city's ability, through a variety of agencies, entities and experts, to organize and run itself) - a concept I will be writing more about in the future.

The backyard of my good friend Simo's building in central Helsinki, with many bicycles.

The backyard of my good friend Simo's building in central Helsinki, with many bicycles. An American composer used the melody in a hymn called This Is My Song (click and take a moment to listen), which I like because it makes clear, in such a beautiful way, the relativity of love of one's country: a recognition that although I may think my country is the most beautiful place in the world, people in other countries believe the same about their own countries.

The following segment of the lyrics brought me to another place:

My country's skies are bluer than the ocean,

and sunlight beams on cloverleaf and pine;

but other lands have sunlight too, and clover,

and skies are everywhere as blue as mine.

Although the sentiments of the song appeal to me, a worrisome realization comes to me that maybe, in fact, skies are bluer in some places than others, at least figuratively.

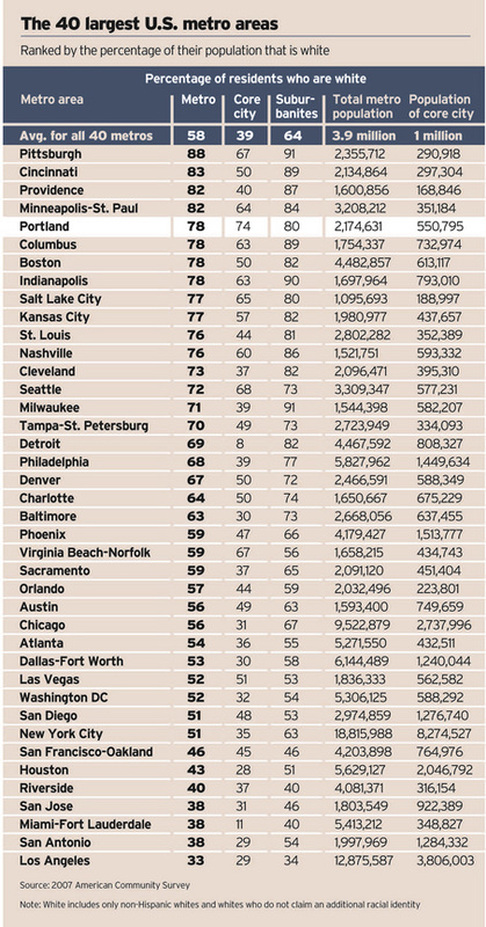

Before coming to Helsinki, I spent over three months in the United States, with long stays in Portland, Oregon and San Francisco, and shorter stays in Chicago, Columbus, Ohio, and New York. Arrival in Helsinki (like arrival in most northern European cities after time in the United States) presents a sharp, uncomplimentary contrast. Americans are often immersed in stunningly shabby physical surroundings, with urban planning and design (not to mention maintenance) decades or more behind other countries at a similar level of economic development. Not only is their physical environment bluntly inferior, but they must contend with systemically ignored, but intense and simmering, social problems which impact security and much else. Because of inadequate investment, public institutions such as schools and government offices are also often poorly run and shabby. This is not an exaggeration. If you have experience between the two worlds, you know what I'm talking about.

If Helsinki and Columbus (cities of very similar size and income level) were two types of cars, Helsinki would be a newish BMW 3-series (the European sort, nothing particularly fancy) and Columbus a 15 or 20 year-old Chevrolet Cavalier. The contrast is truly that profound. The aged condition of the old Cavalier represents the physical infrastructure of American cities. The technology in the car represents the sophistication of its public institutions, and the safety features, the city's crime situation. You might plug some new expensive equipment into the Cavalier - maybe a fancy new stereo or navigation system (which might correspond to a great university or fancy office building in a city) - but you still have the hugely outdated, run-down automobile (and city). The same goes for most other American cities in comparison with cities in the northern areas of Europe, Australia, and the wealthier countries of East Asia. Portland, Oregon may be one of the notable exceptions, but is itself still far behind. It's a national embarrassment for the USA, readily apparent to visitors from other wealthy countries who often are polite enough to say nothing about their surprise to rather patriotic and proud Americans.

This posting on Helsinki will shed some light on what makes for really blue urban skies, and maybe help Americans understand their perennial overcast condition. Please note that I don't revel in my role as an annoying gadfly raising uncomfortable questions about urban life in the USA. How happy I would be if America, instead, were an inspiration to the rest of the world that was leading the way in quality of urban life.

Stone slabs laid with precision between asphalt.

Stone slabs laid with precision between asphalt. An American arriving in Helsinki might experience a certain unease, a sense that something essential is missing. It's that comforting frosting of absolutely featureless, cheap cement covering all surfaces. Its absence will be noted because cement by the square yard is one of those things that makes American cities, well...American.

In Helsinki, a needy cement junkie will have trouble tracking down any reassuringly vast expanses of the substance. It is used commonly in things like highway overpasses (and even here with much more finesse than is the norm in North America), but not in pedestrian areas or generally on streets.

Why is there such a striking difference? A simplified answer that pops into my head is that the appearance of US cities is simply a reflection of American society and its values. Fundamentally, Americans don't care much about how their cities look. Design has given way to expediency. Low cost is the driving force in urban design and maintenance decisions. Americans are happy to accept an unattractive physical environment, with a kind of rough functionality, if that saves them money and allows them to consume more of other things (including fighter jets and missiles). Besides, as they drive rather than walk or bicycle, why worry about the details? In a car-centered society, it's easy for streets to simply become high-speed corridors for driving, with little or no reason to stop and take a stroll.

Another more disturbing possibility is that most Americans simply don't know the difference between good urban design and bad. As they've rarely seen examples of beautifully constructed and managed cityscapes they believe that their streets and pedestrian areas are actually quite nice and as good as (or better than) streetscapes anywhere else. This seems to be confirmed by the boosterism and pride I encounter in American cities. What's most surprising is that many Americans have visited cities abroad with world-class design and infrastructure yet still don't expect or demand such standards at home. This could confirm the notion that they simply aren't able to see the differences and are aesthetically neutered.

A disturbing consequence of America allowing its cities to sink to such a low level is that the skills and craftmanship required to orchestrate and build beautiful streets may have become a lost art in the United States. Even if we wanted to catch up, we would need to import talent to do it right.

Below are some pictures of the beautiful, high quality, and carefully maintained street and sidewalk surfaces in central Helsinki.

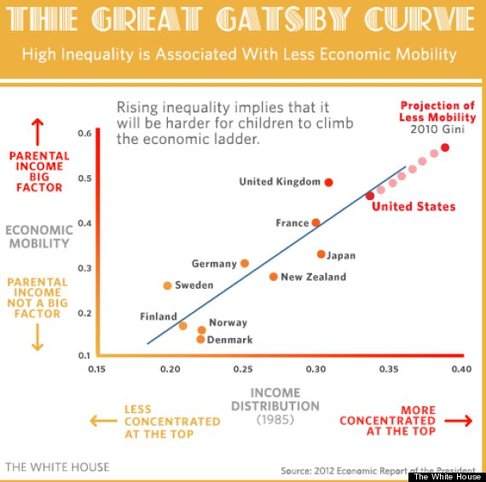

I mentioned above that the car-centered nature of American society might account for the lack of detailed design and attractiveness in its urban streets. But this would hardly explain the parlous state of much of the USA's highway infrastructure. In Finland, highways are smoothly paved and streets do not have potholes. I really don't think I ever saw a pothole on a Helsinki street, and this in a climate that can be brutally cold in the winter. What explanation, I wonder, do American cities give? It certainly isn't that their residents, on average, are poorer than those in their northern European counterparts. Average incomes are rather similar. It may however, be related to the massive inequalities in income which don't show up in typical averages. I will come back to this question later.

The quality Finnish infrastructure extends to bridges, public buildings, sports facilities and even the water pipes that I've seen replaced during construction projects. Below are some scenes of cutting edge infrastructure and architecture that surrounds you in Helsinki.

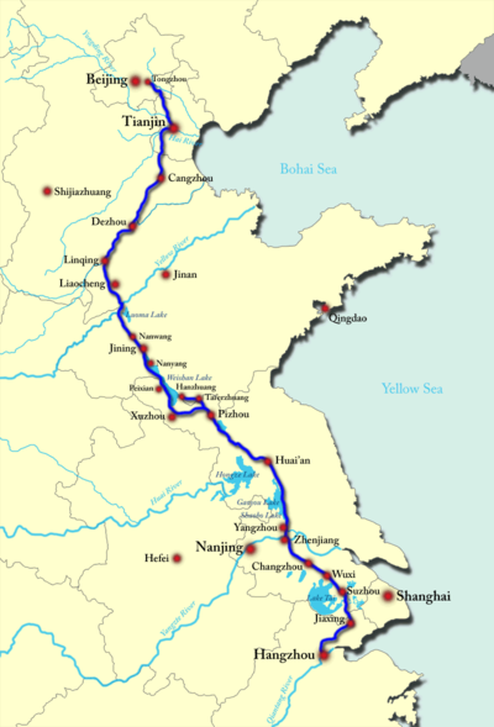

Garden allotments in central Helsinki, in the area known as Central Park

Garden allotments in central Helsinki, in the area known as Central Park From where I lived in the north of Helsinki, in the Paloheinä neighborhood, I could ride my bicycle almost all the way to the center of the city (a 45-minute ride) without ever crossing an intersection and without seeing any cars. This is because Helsinki is designed in such a way that wooded and natural corridors (as well as protected seaside areas) extend like a circulation system throughout and around the city. They give residents quick access not only to peaceful, natural areas but also to safe routes for bicycle commuting . Even Oslo, another city with a wealth of green, doesn't have this same connected system of green spaces and corridors penetrating so deeply into all sections of the city.

My typical ride took me through what is called Helsinki's Central Park, and along the way, I was ceaselessly amazed at the range of uses I found for the open spaces that dominate the city. The pictures below show some of the natural spaces, all without the artificial feeling that over-engineered green spaces often have in cities. They include clean rivers, farmland, vast areas of garden allotments, seashore, and most commonly, forests that go on and on. This despite the fact that the population density in Helsinki is higher than in comparable American cities such as Columbus or Portland.

Bicycle infrastructure in Helsinki seems to be divided into three main types:

1) shared sidewalks (pavements) along streets;

2) shared paths through green areas, and less commonly;

3) dedicated bicycle lanes.

As is common in Norway, Sweden and Finland, most sidewalks along bigger streets are wide enough to accomodate both pedestrians and biyclists. Often there is a line demarcating walking and cycling areas. Just like people walking, bicyclists on shared pavements yield to cars at intersections, although they are generally protected by raised crosswalks that dramatically slow traffic down, making bicycling safe along streets even for children.

The most pleasant, and fastest, way to get around by bike in Helsinki is on the shared paths through green areas, or along the coast. These paths are not specifically for bicycles, and are used by pedestrians, joggers, skateboarders and others (see picture above), and can be covered with asphalt or finely crushed stone. Although they are multi-use, they are almost never crowded and it's very easy to quickly cover large distances, totally isolated from automobile traffic. All streets and roads encountered are either crossed by dedicated bicycle/pedestrian bridges or avoided via underpasses. It's a lovely way to get around as it's safe, you have beautiful scenery all around, and the air is fresh and clean. I used paths like this every day to get into the center of Helsinki.

Helsinki has a few examples of dedicated bicycle lanes, the most interesting bit being the Baana Bicycle Corridor, built along an old rail line. This is a very cool stretch of urban bicycling. Take a look at the link.

The three types of bicycle infrastructure, sadly, disappear in many of the older core neighborhoods of Helsinki. In these areas it's necessary to ride on the cobblestone streets with traffic. If this part of Helsinki were all you saw, you would not think Helsinki is an excellent city for bicyclists - which in fact, it really is.

Not only are forest areas and green belts within a short walking distance of all inhabitants, but there is a very generous allocation of well-maintained playgrounds, sports fields, swimming pools, beach areas. marinas, and more - among the best I've seen anywhere in the world.

Although these facilities are well used, because of their abundance they rarely appeared crowded. There seems to be space for all. I was highly impressed with the quality of materials used and general upkeep.

Below are some pictures of the kinds of generally free, meticulously maintained public facilities that most city-dwelling Americans could only dream of.

Entrance to Helsinki's metro line.

Entrance to Helsinki's metro line. As I was living in a neighborhood far from train, tram, or metro lines, I used bus to get around. Buses were frequent, very clean and pleasant to ride. A nice thing about Helsinki's well-organized bus system is that generally you know rather precisely when the next bus will come. Nearly every bus stop has a digital display that tells you how many minutes before a particular bus arrives. See the middle picture below, showing that bus 63, a line I used frequently, would arrive in 2 minutes. This sort of system is not common in the United States, but it's the norm in much of Europe and East Asia.

Finns are uncomfortable with any suggestion that a class divide exists in this city, but it certainly does. In fact, many of the conurbations outside of center are rather forlorn looking and unattractive. There are signs of social problems such as alcholism and poorly integrated groups of foreigners. What does not exist in Helsinki is a green divide. Even the relatively poor here are blessed with an embarrassment of well-maintained green spaces close at hand.

What struck me most about the lower-class parts of the city is that people are often living in large, high-rise apartment blocks (such as the buildings in the pictures above and below), rather isolated from other buildings, and often quite a walk from any stores. In the summer, it's somehow bearable because of the profusion of green in all directions. But I imagine that in the winter it would be rather bleak, as there is little activity in the environs. Most of these high-rise developments are like islands in the middle of forest. The developments are often centered on a metro stop, where there is always an adjacent shopping center. These commercial centers themselves can be fairly unattractive. I think urban design of this type is a legacy of bad planning ideas from the 1960s and 70s. Most Finns wouldn't want to live in places like this today. However, from disussions I've had with local people involved in urban planning issues, the shopping center-centric style of development continues in Helsinki, continuing to breed car dependancy and continuing to isolate people and deprive them of lively, interesting streets. Timo Hämäläinen writes an interesting blog, called from Rurban to Urban, discussing the challenges Helsinki faces in creating lively, engaging streets and communities.

Below are more examples of high-rise apartment blocks in the east of Helsinki.

Several things strike me about streets in the center. They are:

* narrow sidewalks

* excessive space allocated to car parking

* a lack of trees and other green elements

* a lack of bicycle lanes, and

* a general low level of activity (and hence, perhaps, the perception of tourists that this is a boring city).

In terms of street design in its old urban core (a rather small part of the city), Helsinki is behind the times. The streets, although often lined with beautiful buildings (and also many bland ones erected in a misguided period of urban renewal in the 1960s), lack beauty because so much space is devoted to automobiles. The streets are rather lifeless and drab as there is no leftover space for trees, cafe-lined sidewalks, and bicycle lanes. Wandering these streets in the winter could be quite depressing.

I wonder why so little interesting retail and so few restaurants and cafes line most of these streets. Perhaps there are zoning regulations that keep many business out or maybe high taxes act as a discouragement. It's certainly not that Finland lacks an interesting retail sector. In fact, its shopping centers are full of innovative Nordic chain stores (from Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Finland itself) that would be a hit in the US or other parts of Europe. The outside world only knows about IKEA and H&M, but there is much more. If only Helsinki could manage to get these stores (and restaurants) out of the shopping centers and back onto its streets - this would no longer be a boring city for foreign visitors.

Below, some streets that could use a bit more life (the first from Itäkeskus, a major hub in eastern Helsinki).

Although I love the elegant central districts, with their Jugenstil architecture, the places I find most charming and most uniquely Finnish are the areas of wooden houses and wooden apartment buildings in neighborhoods such as Käpylä and Vallila. It would be a dream for me to have a house in one of these areas.

There's something about these neighborhoods that make you want to settle in. The scale is very human, there's a lot of common green space, and fundamentally, it's just beautiful. Below are some views from Käpylä.

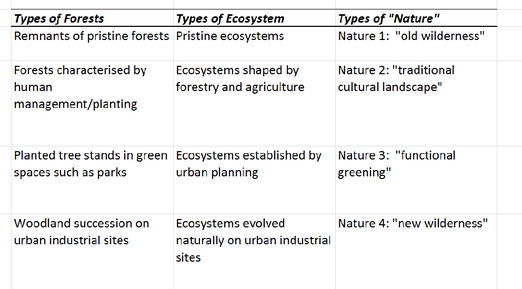

There are many reasons for Helsinki's superiority. One is its outstanding urban organizational competence: Helsinki is a metropolis under professional management and benefits from a highly evolved ecosystem of actors who cooperatively create a great city.

Another underlying reason for its high rank in urban quality of life is the relatively low social inequality, and very high social mobility, in Finland. Residents of Helsinki have a shared destiny and work together to make their city a wonderful place to live. People here are not condemned to an inferior life if they are born in poorer areas. Social mobility is very high.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed