An upper-class neighborhood of Bogotá, with its healthy canopy of street trees

An upper-class neighborhood of Bogotá, with its healthy canopy of street trees My research generated the first set of published data on street-tree inequality in any developing-world city, conclusively demonstrating the green divide in Bogotá and providing a basic model for street-tree equity studies in other cities around the world.

Going down the socioeconomic scale a bit, a street from an upper middle class neighborhood of Bogotá.

Going down the socioeconomic scale a bit, a street from an upper middle class neighborhood of Bogotá. the look of streets as one moves across socioeconomic lines. The change is not striking simply in respect to the style and quality of home and street construction, but equally dramatic in the almost complete lack of street trees and vegetation in

neighborhoods at the lower socioeconomic levels.

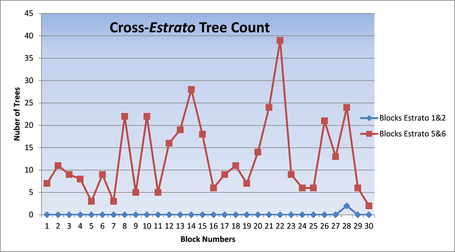

To document the tree disparities across estrato, I conducted a tree survey with a random sampling of 30 streets in the wealthiest part of the city (estratos 5 and 6) and 30 in the poorest parts of the city (estratos 1 and 2). At left is a chart showing the data. The survey results makes it clear that the tree gap across socioeconomic lines in Bogotá is uniform and stark. Generally speaking, the streets in the lowest estrato of Bogotá are barren, while the streets in the wealthy neighborhoods have a healthy canopy of trees.

A typically treeless street in a middle-class neighborhood of Bogotá, far from the poorest.

A typically treeless street in a middle-class neighborhood of Bogotá, far from the poorest.  A rough street in the Kenndy neighborhood of Bogota, with unusually wide sidewalks.

A rough street in the Kenndy neighborhood of Bogota, with unusually wide sidewalks. The problem of the structure of low-strata neighborhoods hangs heavily over efforts to improve the urban environment for the poor, and in particular efforts to increase street-tree cover in Bogotá. As nearly half of Bogotá's

neighborhoods arose from pirate developments, it seems to many that these areas will be permanently treeless. A rebalancing of the tree population in Bogotá’s streets will require strong and effective government and a commitment to focus on the streets that dominate the lives of more than half the population of this city.

To get things moving, highly visible pilot projects should be launched, in conjunction with community organization and green education campaigns, to demonstrate the great improvements in quality of life that green streets can bring. As the streets of most neighborhoods don’t provide much space for trees, innovative and low-cost solutions that provide some of the benefits of trees may be adopted, such as green roofs and vine-covered walls and canopies. However, in many cases as streets are paved for the first time, or repaved, redesigns can be implemented that include planting spaces for trees. In many areas, streets can be pedestrianized, which would allow ample space for canopy-forming trees to be planted. Successful projects showing how city life can be transformed will lead to further interest and belief by the public in the benefits of tree-lined streets. This dynamic city, with its mild and favorable climate, has what it takes to become one of the greenest and most beautiful in South America.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed