The carefully tended Schloßstraße in upscale Steglitz.

The carefully tended Schloßstraße in upscale Steglitz. Berlin's green identity is no accident. There has been a long history of green urban planning, going back to the the late 19th century when Berlin became the new and rapidly growing capital of the German Empire. There was early recognition in Germany that trees and natural spaces could act as a sort of remedy for the ills of 'modern' city life and so they were included in city planning. These natural spaces took the form not only of parks and street trees, but also large segments of the natural landscape on the city's edge and in the suburbs. Berlin is still surrounded by natural woodlands, lakes and fields, all readily accessible by public transport or bicycle.

The relatively desolate Hermanstraße in poor Neukölln.

The relatively desolate Hermanstraße in poor Neukölln.  Muddy path into the mucky edge of Tegel Lake.

Muddy path into the mucky edge of Tegel Lake. An example is the Plötzensee, one of Berlin's most central lakes, in the lower income district of Wedding. This lake is entirely fenced in on all sides, with private beaches and clubs surrounding it. The only 'free' public access is unauthorized access from a very short promenade along one side of the lake. People climb over the railings and enter the lake here. This is not only potentially dangerous, as people are jumping and diving from the railings into the lake (splashing all those around), but the space is so limited that it is almost always extremely crowded, detracting from the positive experience of having a relaxing time at the lake. There is little space to stretch out and sunbathe along the side of the lake, only a small, very worn grassy area in front of the promenade. I found a similar situation at other Berlin lakes I've visited. The picture above shows my entry point into Tegel Lake yesterday, also in the north of Berlin. I was with my friend Yasuko, and we watched two wincing Spanish women wading through the muddy bottom to get to deeper water to swim. We winced a bit, too, but enjoyed our swim in the seemingly very clean water filled with many fish. Let me add here that I've been told about ongoing efforts to expand public access to the Berlin waterfront, and slow progress is being made.

A gravel road in a dense forest in the north of Berlin

A gravel road in a dense forest in the north of Berlin  Plaza upgrade underway on the rather depressing Karl Marx Straße in Neukölln.

Plaza upgrade underway on the rather depressing Karl Marx Straße in Neukölln. Initially, a green movement emerged that saw this destruction as a blessing in disguise. The worst of the damage to the city had occurred in the central districts, the very districts where high density housing for the working class often existed. It became fashionable for planners to envision a 'loosened' city, where open green spaces would be reintroduced to the dense center resulting in a more 'organic' structure of the central city.

Rebuilt apartment building from 'building program' of 1950.

Rebuilt apartment building from 'building program' of 1950. The political and later physical division of the city also limited the amount of land available for development in the West, leading to a pragmatic shift in planning away from nature towards economic and social development on the spaces left open after the war. In the East there were far fewer resources available for development of any kind, and it lagged far behind the West in both green and social investment.

A former runway at Tempelhof on a sultry July day.

A former runway at Tempelhof on a sultry July day. One route runs very near my apartment and continues on through Tempelhof Feld (photo above), the former airport made famous in the Berlin Airlift. I ride on it nearly every day. Tempelhof Feld, a huge open space of grassy meadows and wide car-less surfaces of cement and asphalt, resulted from the decommissioning of the airport. It's just another example of the growing collection of vasts open and green areas of which Berlin can be proud. It directly abuts areas of lower socioeconomic level, and is filled every summer day with young people relaxing and drinking beer, picnickers, Turkish families enjoying a barbecue, and even wind surfers.

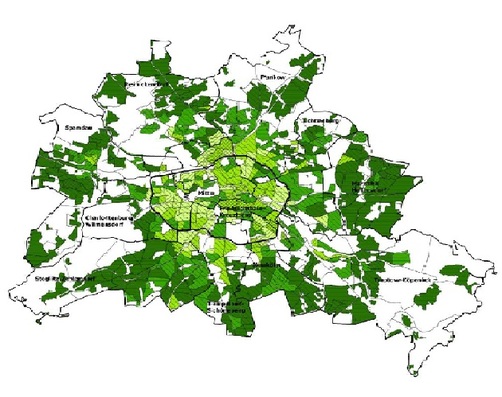

Data map of Berliners access to green space. Lighter green = lower access.

Data map of Berliners access to green space. Lighter green = lower access. Urban environmental justice, and the green divide, is best addressed when approached as a multidimensional issue with the support of multiple disciplines. Very few large cities in the world are as well-equipped as Berlin to meet the challenges environmental inequities raise. The steady progress of environmental improvements in this city can serve as a model to other cities around the world.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed