Fourth Nature on Display

Fourth Nature on Display At the end of World War II Berlin found itself in an odd situation. It was a divided city, ultimately between an East German controlled East and a West German controlled West. This division separated the city not only politically, but also in terms of ecological study and practice. The universities and practitioners in the western part of the city gradually became more and more detached from those in the eastern part, especially after the wall went up. What's more, with the erection of the wall and strict travel restrictions, ecologists in the West were deprived of access to Berlin's green hinterland, the countryside surrounding Berlin, their traditional area of research. This left ecologists and natural scientists with a greatly restricted area for research and ultimately redirected a group of them to the variety of open spaces within the city itself that supported nature. Berlin had a large number of new habitats for these researchers to examine: large tracts of empty land left over from destroyed buildings (rubble fields, really) and abandoned industrial infrastructure which were gradually being recolonized by vegetation and wildlife.

The old Baumgarten villa

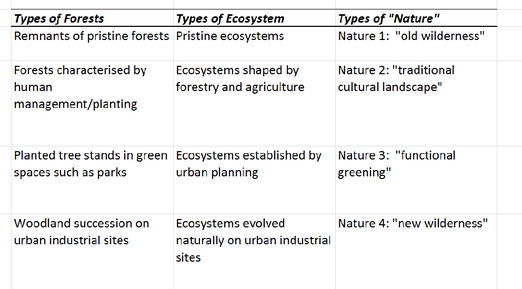

The old Baumgarten villa  Simplified chart from a paper by Dr. Kowarik.

Simplified chart from a paper by Dr. Kowarik.  Südgelände railyard in 1935

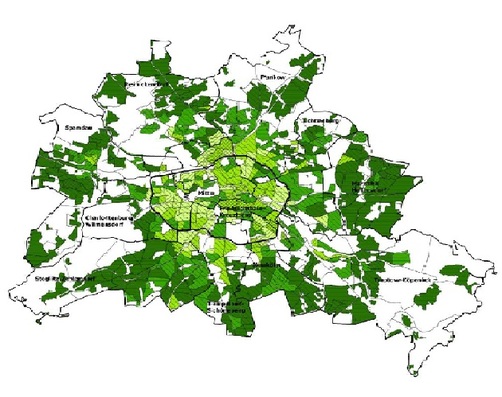

Südgelände railyard in 1935  Professor Wiedenmann: Part of Berlin 'Ecosystem'

Professor Wiedenmann: Part of Berlin 'Ecosystem' The lessons of 4th Nature parks for rust-belt cities in the US, and other declining industrial cities, are great. Berlin makes me think a lot about Detroit (which in some ways resembles Berlin after the war), and I imagine there must be a huge potential for 4th Nature parks in that city.

More sharing of best practices like this are required throughout the world, but especially in the developing world where cities have limited space and resources. 4th Nature parks use abandoned land that is often unsuited for other types of development and are relatively inexpensive to develop and maintain. This is just one great innovation that I've learned about in Germany.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed